Authors: Andrea Olmedo and Mar Escarrabill

Technological advances and social changes in information and communication technologies (ICT) have led to the consolidation of informationalism. According to the sociologist Manuel Castells, this is the technical paradigm of contemporary network societies.[1] Ubiquitous computing and the mobile communications (MC’s), particularly locative media, have become a massive phenomenon and one of the pillars for the contemporary platform economies. This is specially significative in the health field where ICT has a huge impact and the number of apps is growing significantly. MC’s at that field have shown some benefits for their users in terms of medical education and training, communications and consulting or patient monitoring. However, this privative model based on data collection had also raised many ethical and political dilemmas regarding its inclusion/exclusion dynamics, the privacy of this sensitive data and the lack of mediation between data and users. Interestingly, many researchers, practitioners, artists, activists and patients overcome these MC’s dilemmas by co-creating initiatives that use the collected health data to achieve a collective well-being. By studying these initiatives, we wonder: Can we find commons-inspired health and care projects that use locative media? Blind Wiki, Humanitarian Open Street Maps and Quipu Project give us some inspiring ideas to explore the crossroad between locative media, health and commons.

The benefits of MC’s can be clearly seen in the field of healthcare, where advances in ICT have a deep impact. Nanotechnology, bio monitoring, pervasive computing, wearable systems, drug delivery or mobile communication are some examples of this healthcare sector transformation. According to Pelin Arslan from the MIT Mobile Experience Laboratory, advances in the use of ICT make possible a better capture and analysis of individual’s socio-psychological environment. Moreover, this allows them to integrate with other quantified datasets for better decisions.[2]

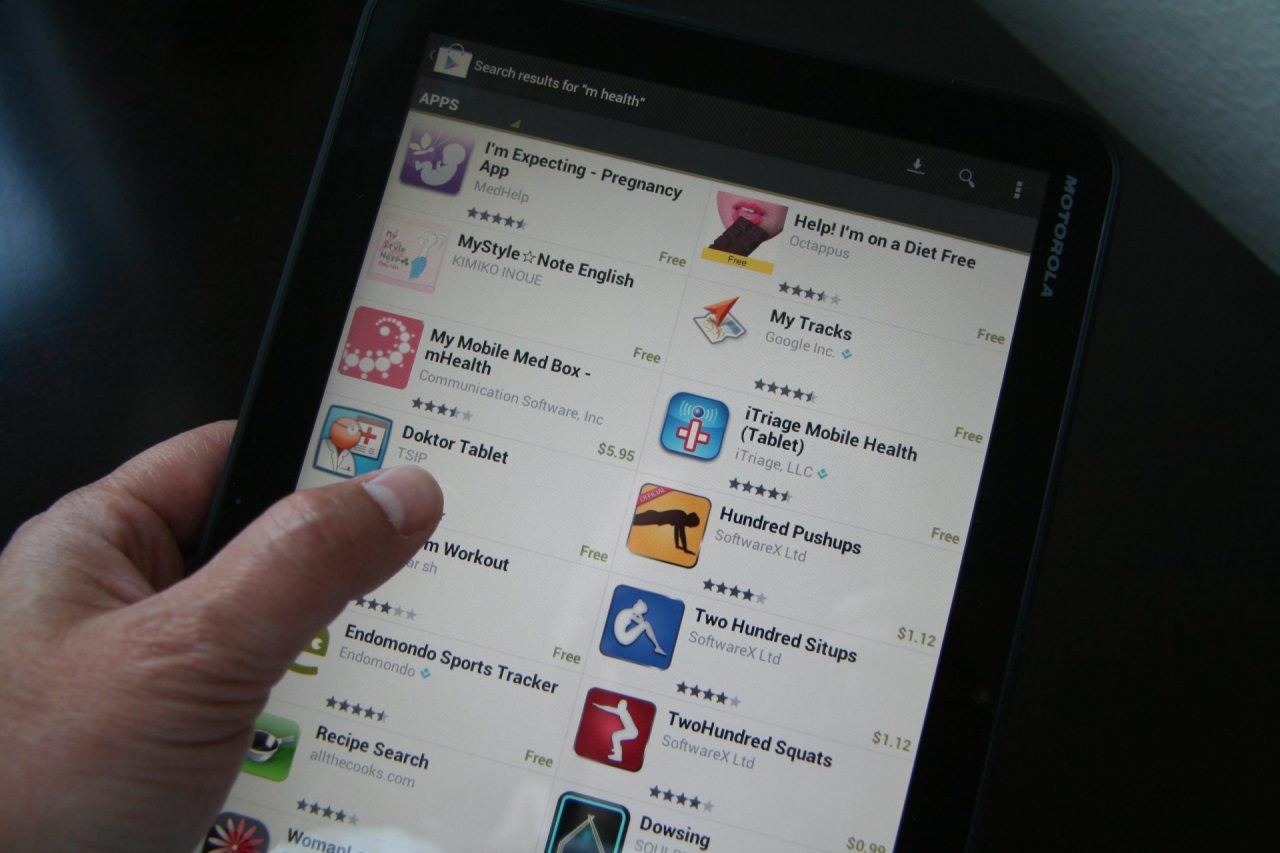

A plethora of healthcare mobile apps are developed on a daily basis. According to the researcher and medical writer C. Lee Ventola[3], mobile technologies in healthcare are mainly related to health record maintenance and access (a.o. MyFitnessPal), communications and consulting (e.g. Doximity), patient management and monitoring (such as Seizure Tracker), clinical decision-making (such as MDCalc) or medical education and training (a.o. QuantiaMD).

Although some healthcare apps may benefit their users many ethical and political problems can emerge in this ecosystem in which new players co-exist and interact. According to Castells, the self-expanding capacity of processing (in terms of storage and speed), the recurrent communicative capacities (in terms of feedback) and their emergent enhancements are the main defining features of these networks. Also, the structural dynamics of inclusion and exclusion to them.

In addition to the digital break, we find other ethical problems that are mainly linked to the privative model of data collection in such a sensitive field as health. As an example, we could mention the period-tracking apps (such as Clue[4]) that creates consumer profiles for use in targeted ads according to the intimate data that women share in the app. It does not comes as a surprise that our main concerns are related to the data ownership and the purpose of this exhaustive collecting. According to the medicine professor Michael L. Millenson[5], these digital datasets may be used to manipulate, target or manage people profiles. In most cases these interactions don’t contemplate the social determinants of health and, contrary, perpetuate existing social injustices and disadvantages. Finally we found there is not a human mediation between the person and the application feedback to ensure the understandability of the gathered data and to avoid possible manipulations.

Contrary to the above mentioned healthcare approach, a network of activists, researchers, artists and practitioners are working around the globe for a commons care infrastructure using new technologies with ethical values. Their initiatives do not understand health data as currency for platform economies corporations or healthcare as an individual problem. Instead, they explore creative ways to share health-related knowledge, establish support networks for people affected and act collectively to preserve the right for health as a common good.

Commons are shared resources managed by communities through a set of social norms jointly agreed. According to the activist, writer and producer David Bollier[6], the sum of shared resources, community and a set of norms gives rise to a self-organized social system with internal dynamics. This concept is not new, human beings have used it for millennia to meet their needs. Commons stimulate social relations through collaboration in a context that lets people decide collectively on the rules for managing the resources in which they depend.

Communal governance experiences, can provide us a “know how” and tools to build networks that give participating members a significant degree of sovereignty and control over important elements of their everyday lives. The self-organization principles of the commons have been studied in depth to reflect on the governance of rural lands or data. However, its relation to health has not been extensively explored. A commons-inspired healthcare approach can avoid top-down services that can induce barriers of access or participation. This approach allows to grow decentralized networks coordinated by a wider range of actors that collectively care: public administration, civil society, people affected and their families, research groups, industry, etc.

A great example of a commons approach in health are the Pirate Carers, a concept introduced by the researcher in post-digital cultures Valeria Graziano.[7] These technologically-enabled care agents emerged in opposition to the increasing privatization of basic care provisions that deny its access to those who lack the financial resources. Ambulatorio Medico Popolare, GynePunk or CADUS are some projects of this caring movement. All of them are inspired by the principles of self-organization and promote a human centered healthcare through a commons approach.

The intersection between locative media, health and commons is complex and unexplored. What do we understand by locative media, health and commons in our study?

Locative media is a category to designate processes, prototypes and applications that are based on the interaction of the screen interface with the here and now of the urban space.[8] Both parts, interface and physical space, melt in a hybrid space: one is the extension of the other one. The main particularity of locative media is that require user’s location to give access to information. So the actions and movements on public space become storable and shareable. Our approach for this research will include also telematic local media projects. Thus, we will add the ones that for a lack of accessibility of the participants chosen different technological strategies.

As we mentioned, commons are shared resources self-managed by the community involved through a set of norms collectively agreed. We’ve also opened our analysis to procommons: all the initiatives that without following a strictly commons structure (e.g. being a cooperative) are also working for the commons in their actions. Thus, we’ve distinguished between the team core organization (that can not have a commons structure) and the project itself (that can work actively for the commons). These initiatives emphasize the collective management of resources and focus on open and shared replicable tools in order to guarantee its access.

In terms of health we are especially interested in those initiatives referring to a feminist approach to the physical and emotional well-being of people necessary for a worthy life. With this approach, we also focus on all those that combat health inequalities and work to mitigate the social determinants of health (a.o. poverty, social exclusion, employment conditions or environment conditions).[9]

According with the intersection proposed, citizen’s wellbeing is a collective responsibility, caring has a central role in our daily life and locative media can be an exploratory strategy to address these challenges. In this context, establishing communitarian governance strategies can be of interest to launch initiatives that operate into these spheres. An inspiring example is found in the Transborder Immigrant Tool, a project launched in 2007 by the artistic group Electronic Disturbance Theater. This app facilitates the access to resources to make the border crossing between Mexico and the United States safer, giving, among others, the location of infraestructures or the safest routes.

Bellow, we introduce three current projects that operate in this intersection: Blind Wiki, Humanitarian Open Street Maps and Quipu Project. We’ve explored them through guided conversations with three enthusiastic people involved in them: the artist Antoni Abad from Blind Wiki, Paul Uithol, project manager of Humanitarian Open Street Maps and the documentalist Rosemarie Lerner from Quipu Project. Their expertise can help us to delve more in depth into this unexplored crossroad.

Blind Wiki is a location-based audio network where citizens that happens to be blind use locative media to share their experiences regarding public space by posting in situ voice notes. The project facilitates a media that not just contain information about accessibility but also a repository for their located feelings, opinions and stories. They co-create this media by mapping while taking decisions about the topics that they want to talk about, the taxonomy system, and the places mapped.

The project was promoted by the Catalan artist Antoni Abad in 2014. Since 2004 he has been working with Megaphone, a locative media art work based on collaborative webcasting. This initiative amplifies the voice of communities in risk of social exclusion and mediate between them and the rest of the society for being heard.

We find the most interesting contribution as an artistic project is its experimentation on collective “data sensorialitzation” into a dialogic art proposal that needs the participants interaction to be performed.

Humanitarian Open Street Maps (HOT) is an international network dedicated to prevent and help in humanitarian action. HOT creates projects that focus on communitarian development. They use the potential of Information Geographic Systems to create a distributed platform to work with local communities and online mappers. The aim is to provide helpful map data to act in disaster management and to reduce risks for the population and environment. HOT brings strategic resources, infrastructures and local and mobile humanitarian services.

The project started in 2009 and is developed by an international community run by almost two hundred thousands volunteers, local communities, and different professionals. Just in the past three years, they supported 24 communities across 22 countries.

We think that one of the strengths of the project is its distributed and well documented platform that allow people to work together online and offline in extreme conditions.

Quipu Project is an audio-based online documentary that collect and make visible the stories and memories of nearly three hundred thousand of indigenous people living in rural areas, mostly women. They are the victims of a forced sterilization program of the Peruvian State under Alberto Fujimori presidency in the 90s decade. The aim of the project is to build up a community around the muted conflict in order to internationalize it and force public agendas to initiate a reparation process. They facilitated a phone number with an answering machine to record the testimonies in various parts of the country.

The project is an initiative of the documentary filmmakers Rosemarie Lerner from Peru and Maria Court from Chile that opened it to the public in 2015. After that they made a huge communication campaign and a linear documentary film.

We consider that one of the most attractive parts of the project is the process itself, the field work with rural communities and the careful listening to their needs.

From different fields as digital arts, Geographic Information Systems (SIG) and participatory documentary, Blind Wiki, HOT and Quipu Project have reached transdisciplinary approaches. All of them are procommons projects that listen deeply to the context where they work to intervene on it and meet the needs of vulnerable communities. Also, their coordinators develop enunciation spaces for talking and being listened: between people that happens to be blind and their social environment, among people affected by humanitarian crises and within rural women affected by forced sterilizations.

All the projects mediate inside specific groups, between different ones and with public institutions. They bring bottom-up initiatives that facilitate the feedback between offline and online spaces. Blind Wiki, HOT and Quipu build co-creation processes in which affected people become co-author of the data and the media itself. Also, they focus not only in the data, but in the narrative and the stories.

Their teams try to be transparent with its governance. Moreover, they emphasize the use of FLOSS and facilitate technology self-inclusion, particularly to those affected by technological gaps. The projects have strategies for disseminate their results and create new networks. In addition, they facilitate not translations but transductions. Finally, they contribute to mitigate the social determinants of health and, far from apps that individualize health issues, understand health as a social responsibility.

How Blind Wiki, HOT and Quipu Project understand and address all these goals? Which strategies undertake? What kind of methodologies, tools and technologies are developed for each project? What challenges did they find? How they tackled them? What can you learn from them if you want to develop a project in this -as we found- rich intersection of locative media and health care with a commons perspective? The guidelines to work in this intersection learned from our talks with Blind Wiki, HOT and Quipu will be published soon! Stay tuned!